|

Gargoyle |

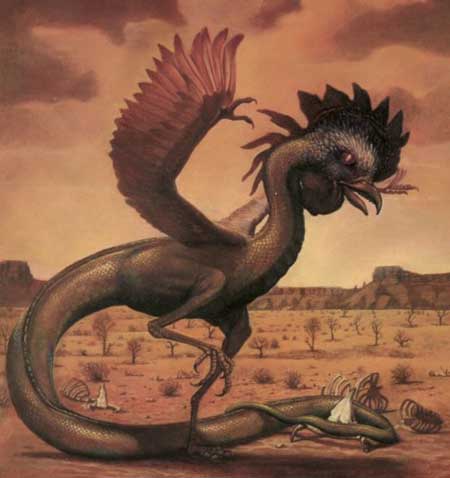

Assorted DemonsBasilisk

The name basilisk

comes from the Greek basileus,

Two artists conceptions are shown here.The basilisk was depicted in a few illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages but appeared much more often as an ornamental detail in church architecture, adorning capitals and medallions. The best representation of the basilisk is found in the decorative field of heraldry where the basilisk had the head and legs of a cock, a snake-like tail, and a body like a bird’s. It seems that the wings could be depicted as either being covered with feathers or scales

Traditional myths define the Basilisk as a "poisonous worm and fable emerging from the egg of an old rooster, brooded by the warmth of dung or by a snake or a toad.". The appearance of the Basilisk is described as "like a cock with dragon's wings, the beak of an eagle and the tail of a lizard."

The antique Romans

called him "regulus" or little king, not only because of his crown,

but because he terrorized all other creatures with his deadly look

and poison. His color was yellow, sometimes with a kind of blackish

hue. Plinius mentioned a white spot on his head, which could be

misinterpreted as a diadem or a crown. Others speak of three spikes

on his forehead. Regarding his dangerousness rural legends distinguishes three main types. All three had a deadly breath, which could even make rocks crumble.

The final image is the coat of arms of the House of Visconti, on the Archbishops' palace in Piazza Duomo, in Milan, Italy. In this image it is evident that the heraldic animal of the House of Visconti is a basilisk

Gargoyle

Two sample of Gargoyles are shown, one at the top of the page and the other to

the right. The term originates from the French gargouille, which

in English is likely to mean "throat" or is otherwise known as the "gullet".

Gargoyles are often used as water spouts on buildings. Others, like

the two shown here are for decoration. A French legend that sprang up around the name of St. Romanus ("Romain") (AD 631–641), the former chancellor of the Merovingian king Clotaire II who was made bishop of Rouen, relates how he delivered the country around Rouen from a monster called Gargouille or Goji. La Gargouille is said to have been the typical dragon with batlike wings, a long neck, and the ability to breathe fire from its mouth. There are multiple versions of the story, either that St. Romanus subdued the creature with a crucifix, or he captured the creature with the help of the only volunteer, a condemned man. In each, the monster is led back to Rouen and burned, but its head and neck would not burn due to being tempered by its own fire breath. The head was then mounted on the walls of the newly built church to scare off evil spirits, and used for protection.[4] In commemoration of St. Romain, the Archbishops of Rouen were granted the right to set a prisoner free on the day that the reliquary of the saint was carried in procession (see details at Rouen). Gargoyles were viewed in two ways by the church throughout history. The primary use was to convey the concept of evil through the form of the gargoyle, which was especially useful in sending a stark message to the common people, most of whom were illiterate. Gargoyles also are said to scare evil spirits away from the church, this reassured congregants that evil was kept outside of the church’s walls.[9] However, some medieval clergy viewed gargoyles as a form of idolatry. In the 12th century St. Bernard of Clairvaux was famous for speaking out against gargoyles. GremlinsAlthough their origin is found in myths, Airmen, claiming that the gremlins were responsible for sabotaging aircraft, John W. Hazen states that "some people" derive the name from the Old English word gremian, "to vex". Since World War II, different fantastical creatures have been referred to as gremlins, bearing varying degrees of resemblance to the originals.

An early reference to the gremlin is in aviator Pauline Gower 's The ATA: Women with Wings (1938) where Scotland is described as "gremlin country", a mystical and rugged territory where scissor-wielding gremlins cut the wires of biplanes when unsuspecting pilots were about. An article by Hubert Griffith in the servicemen's fortnightly Royal Air Force Journal dated 18 April 1942, also chronicles the appearance of gremlins, although the article states the stories had been in existence for several years, with later recollections of it having been told by Battle of Britain Spitfire pilots as early as 1940.] This concept of gremlins was popularized during World War II among airmen of the UK's RAF units, in particular the men of the high-altitude Photographic Reconnaissance Units (PRU) of RAF Benson, RAF Wick and RAF St Eval. The flight crews blamed gremlins for otherwise inexplicable accidents which sometimes occurred during their flights. Gremlins were also thought at one point to have enemy sympathies, but investigations revealed that enemy aircraft had similar and equally inexplicable mechanical problems. As such, gremlins were portrayed as being equal opportunity tricksters, taking no sides in the conflict, and acting out their mischief from their own self-interest. In reality, the gremlins were a form of "buck passing" or deflecting blame. This led folklorist John Hazen to note that "the gremlin has been looked on as new phenomenon, a product of the machine age—the age of air". This explanation from Wikipedia ignores the fact that Gremlins were depicted in Medieval times as shown in the carving here on Notre Dame Cathedral built long before the age of airplanes. Gremlin lore has spread far and wide through books and film.

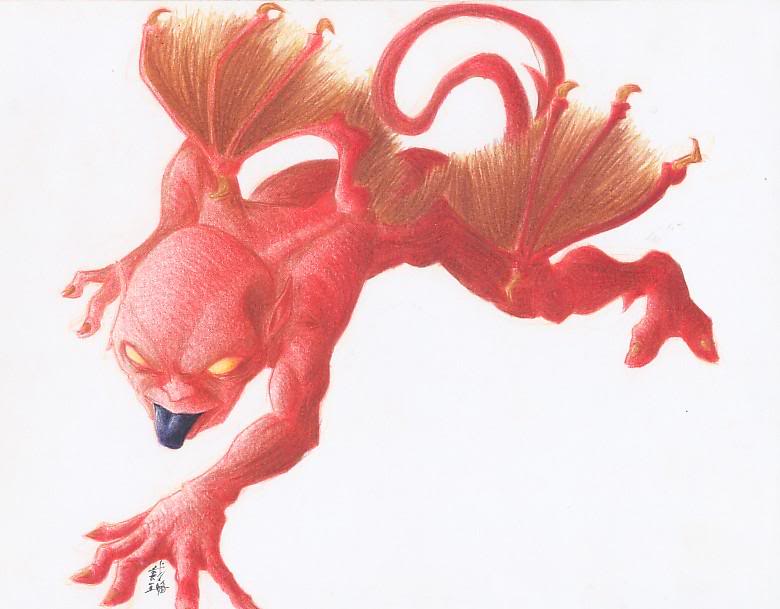

Foliot

A few historical references.

FOLIOT - fó'l-ýót, n. A kind of demon

Fo'liot [Ital. foletio, "a spirit, a

hobgoblin, a robin-goodfellow," Florio World of Words 1598.] A kind

of demon.

Where it falls in demon ranks (listed higher

order to lower): Perhaps because higher order demons are more powerful and their feats are better known, there isn't a lot written about foliot characteristics. Nor are there many depictions in history or on the web. |

|

| Web Design by Mike Lance | |